- Home

- Nancy Jo Sales

The Bling Ring Page 2

The Bling Ring Read online

Page 2

When Nick checked out the aerial shots of the Mulholland Estates, he noticed an area in the back that looked accessible via a steep hill. Rachel was pleased with this finding, he said, and that pleased him; Nick liked to please Rachel. He felt a thrill as they hurtled toward this strange adventure together. He was nervous, he said, but Rachel was calm, and that calmed him down. He tried to keep his mind on the music playing in the car as they zoomed along through the dark. He liked club hits by Pharrell and Lil Wayne and songs by Atmosphere, the melancholy white rap group from Minnesota. There was one song of theirs in particular that always made him think of Rachel—called “She’s Enough.” It’s about a man who will do anything for the woman he loves:

“If she want it/I’m gonna give it up . . . If she needed the money/I would stick you up . . . She wanna do the damn thing and I’m on her side . . .”

Around midnight, Nick said, they arrived at the Mulholland Estates and he parked his white Toyota at the back of the development. They found the hill they were looking for easily and climbed it, making use of the smooth firebreaks—man-made clearings in its side—to help them scale it. They could hear each other panting with the effort. They weren’t athletic kids—they smoked cigarettes and weed. They both had medical marijuana cards issued by the state of California; they weren’t hard to get.

Once inside the gated community, they strolled past the cavernous castle-like mansions and gleaming luxury cars, as if in a dream. They were confident, Nick said, that if anyone spotted them, they wouldn’t be thought out of place. They looked like “normal kids”; he might be some neighbor’s boy; Rachel might be his girlfriend.

“That’s the thing that really made everything flow when me and Rachel would go out and do these things,” Nick said. “We wouldn’t be masked, we wouldn’t be in gloves. We wouldn’t be conspicuous—we’d be just natural looking so if anything ever happened we’d just be like, what? We’re normal kids. It wasn’t that we were criminals.”

He said he could never remember the exact moment when he and Rachel decided to start burglarizing the homes of celebrities; but once they did, they knew right away that Paris would be the first. “Rachel’s idea,” he said, “and, I guess, my idea, was that she was dumb. Like, who would leave a door unlocked? Who would have a lot of money lying around? Logically out of anyone in America could probably figure out that if you were gonna do something to a celebrity it would be someone that wasn’t, you know, that bright. . . .”

And then suddenly there was Paris’ house, rising before them like the villa of some Spanish contessa, all glowing yellow stone and Mediterranean tile. Nick tried to stay calm as he followed Rachel across the driveway to the front door. Their plan—well, not really a plan, it was more of an impulse, for as often as they had imagined this night, they had actually decided to just go and do it spontaneously, after having a few drinks—their plan was just to ring the bell and see if anybody answered. And if somebody did, well, then, they might get to see Paris. And that would be awesome, in a funny kind of way. They would pretend they were just a couple of ditzy kids with the wrong address, kids out looking for a party.

Rachel rang the bell, Nick said, putting on the innocent face he had seen her wear so many times before. Rachel was good at playing the pretty girl whenever adults were around asking questions. “She knew she was a good-looking girl and she knew there were certain things she could get away with. She knew how the system worked. She knew how you could play it.”

She rang and rang again . . . but still there was no answer. Was Paris in, or out? Promoting her handbag line at some Tokyo department store? Attending a Russian billionaire’s birthday party in Moscow (for a fee, of course)? Nick had been tracking Hilton’s whereabouts through her Twitter account and celebrity news outlets like TMZ, but he wasn’t actually sure where she was that night. . . .

Ding-dong.

Were they really going to do this thing? Or were they just going to go home with a funny story to tell their friends?

And then, Nick said, the thought occurred to him just to look under the mat. It was like finding Willy Wonka’s Golden Ticket when the glinting metal of the key appeared. Dumb was right.

“Wow.”

Inside it was like a Barbie Dreamhouse. There were images of Paris everywhere, framed photographs of Paris on the walls; framed magazine covers of Paris cover stories; framed pictures on tables of Paris with all her famous friends—there was Mariah Carey, Jessica Simpson, Fergie, Nicky Hilton (Paris’ sister), Nicole Richie (were they still close?). There were pictures of Paris in the bathrooms. Her face was silkscreened on couch pillows.

There was a lot of pink, and there were crystal chandeliers in almost every room. Even the kitchen. It was like stepping into the girliest Hilton hotel you’ve ever seen. Nick said they walked around slowly, marveling that they were really there. “There was that percentage of wow, this is Paris Hilton’s house, but as soon as I put my foot in the door, I was just wanting to run out. . . .It was horrifying.”

He wanted to leave, he said, but now Rachel was running up the stairs. Upstairs were the bedrooms, and the bedrooms had the closets, and the closets had the clothes. Nick said he followed Rachel to the master bedroom—it was chilly in there and smelled like the perfume counter in a department store. The room led out on to a balcony overlooking the pool and, beyond that, the rolling hills of the Valley, shimmering with lights. As they gazed in the direction of their own homes from the vantage point of one of the most Googled people on the planet, they couldn’t help but laugh.

The little dogs—Chihuahuas and a Pomeranian, Tinkerbell, Marilyn Monroe, Prince Baby Bear, Harajuku Bitch, Dolce and Prada—scurried around, regarding them curiously, but they didn’t bark. They must have been used to having strangers in the house. (About a year later, Hilton would build the dogs a 300-square-foot, $325,000 miniature of her home in the backyard. Philippe Starck would provide the furniture.)

“Oh my God!”

Nick said that Rachel squealed with delight when she found the closets. One was the size of a small room and the other the size of a small clothing store. It was like that scene where the dwarves discover the dragon’s treasure-laden lair in The Hobbit. One closet had a chandelier, and the other had furniture, as if Paris might want to just sit in there and look at all her stuff. The smaller closet had floor-to-ceiling shelves with hundreds of pairs of shoes, all lined up like trophies—Manolos, Louboutins, Jimmy Choos, a pair of YSLs shaped like the Eiffel Tower. There were shoes of every color—satiny, shiny, pointy shoes. Huge shoes. Size 11.

The bigger closet was full of racks and racks of clothes. Nick had to smile. “Rachel, do your thing,” he said. And “she was rummaging through everything, very, very into it, very focused, very ‘This is my mission.’ ” She was plowing through the racks of the wild, sparkly, feathery clothing, exclaiming over all the designers—this was Ungaro, that was Chanel! There were dresses, gowns, blouses, and coats by Roberto Cavalli and Dolce & Gabbana and Versace and Diane von Furstenberg and Prada. . . . Nick said Rachel recognized some of the pieces from Paris’ public appearances; she followed these things; she knew which one Paris had worn to the VMAs and the Teen Choice Awards.

He said she said it was like “going shopping.”

Now he was starting to get nervous again. He decided to go and be the lookout from the top of the stairs; from there, you could see through the big windows to the front of the house. So Nick stationed himself there. He was “sweating unnaturally,” he said. “Every five minutes I was yelling down the hall, ‘Let’s get the fuck out of here! I want to leave! Fuck this, I don’t care anymore!’ And she was like, it’s fine, it’s fine, it’s fine, let’s keep going. . . .”

He resented the way that Rachel was always in charge, no matter what they did—he “hated that,” he said—but what could he do? This was “the girl [he] loved,” and he didn’t want to lose her. And although he’d never tested it, there was something about Rachel that said that if you didn’t d

o what Rachel wanted, she would walk. It wasn’t that he minded Rachel taking a few of Paris’s things—look at Paris’s house; she “had everything.” And she “didn’t really to contribute to society,” she wasn’t “some great actor like Anthony Hopkins or Johnny Depp, someone that’s really good at their craft.” She was an “heir head,” like the tabloids said, a “celebutard.”

“It wasn’t like a malicious thing for me,” Nick said. “I wasn’t out to get, like, a working-class American.”

But Nick did not want to get caught. He yelled again for Rachel to “hurry up and let’s get out of here!” But he said she just answered, “This is fine, this is okay, why are you tripping out?”

And then he saw on the wall of the stairwell the portrait of Paris scowling down at him. She was wearing a little black cocktail dress and sitting on a settee with her legs folded underneath her. She looked like a Park Avenue princess who has become very displeased about something. She was staring, glaring, as if to say, “How dare you come in my house and touch my stuff, bitch? I’m gonna get you. . . .”

Nick bolted back down the hall to Rachel. She had selected a designer dress, he said—he couldn’t remember which, “there would be so many”—and a couple of Paris’ bras. He insisted that now it was time to leave—but not before they checked inside Paris’ purses. They knew from experience—for yes, they’d done this kind of thing before—that people with money tend to leave money lying around the house. And, sure enough, in the closet with the shoes and the sunglasses where Paris also kept her many bags—Fendi, Hermes, Balenciaga, Gucci, Louis Vuitton and on and on—they found “crumpled up cash, fifties, hundreds,” “which looked to us like she went shopping that day, and this was just her spare change.” Nick would remember the smell of the expensive leather, Rachel oohing and aahing over the labels, and the crinkling sound of the bills. They came away with about $1,800 each—a good haul.

And now it really was time to go. But first they couldn’t resist checking out the rest of the house. They wandered around—it was spooky, as if Paris were there somewhere, watching them. Paris could walk in at any time. They discovered the nightclub room with the disco ball and the padded bar. They thought about all the famous people who had been in there—Britney, Lindsay, Nicole, Nicky, Benji Madden (the Good Charlotte guitarist and then Paris’s boyfriend), Avril Lavigne. . . . They couldn’t help but imagine themselves there again someday, chilling, dancing, with Paris.

Nick took a bottle of Grey Goose vodka for himself, and they left.

2

About a year later, in October 2009, I found myself driving along the 101 North from L.A., on my way to Calabasas. It was a fine, clear day. I had a cup of coffee in the cup holder beside me, traffic was humming, and the craggy Santa Monica Mountains lay before me like giant scoops of butter pecan ice cream. They were kind of pretty, and that was not what I was expecting. I’d never been to the Valley before. All I knew was its reputation, that it was the West Coast’s bookend to New Jersey, a place full of shopping malls and spoiled teens speaking Valley Girl. Bob Hope, a Valley resident for more than sixty years, had called it “Cleveland with palm trees.”

Vanity Fair had put me on the story of “the Bling Ring”—that was what the Los Angeles Times was calling a band of teenaged thieves that had been caught burglarizing the homes of Young Hollywood. Between October 2008 and August 2009, the bandits had allegedly stolen close to $3 million in clothes, cash, jewelry, handbags, luggage, and art from a number of young celebrities including Paris Hilton, Lindsay Lohan, and Pirates of the Caribbean star Orlando Bloom. They’d stolen a Sig Sauer .380 semi-automatic handgun that belonged to former Beverly Hills, 90210 cast member Brian Austin Green. They’d taken intimate things: makeup and underwear. It seemed they just wanted to own them, wear them.

The Bling Ring kids were from Calabasas, a ritzy suburb about thirty minutes from L.A., and that’s why I was headed there. There’d never been a successful burglary ring in Hollywood before, and somehow it made sense that it would be a bunch of Valley kids. I wasn’t sure why it did, but I thought if I went to Calabasas I might find out.

Up until the 1940s, I’d read, the Valley was “out there,” ranchland where settlers went to grow oranges and raise chickens and families. Then Hollywood discovered it as an appealing hideaway with bigger houses—Clark Gable and Carole Lombard made a love nest there, and so did Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. Jimmy Cagney moved out to play gentleman farmer, Barbara Stanwyck to run a thoroughbred ranch, but somehow the place never became glamorous. Something was always off. After the war, the population exploded, and the Valley became the defining American suburb, a sunny Eden of split-level homes, electric blue swimming pools, and kids living seemingly perfect childhoods. The Brady Bunch were tacitly Valley folk.

Frank Zappa’s song “Valley Girl” (1982) introduced the world to a young white Southern California female whose main interests were shopping, pedicures, and social status: “On Ventura, there she goes/She just bought some bitchen clothes/Tosses her head ’n flips her hair/She got a whole bunch of nothin’ in there. . . .” Zappa learned about Valley Girls from his then 14-year-old daughter Moon Unit, who encountered them at parties, bar mitzvahs, and the Galleria mall in Sherman Oaks. The film Valley Girl, released in 1983—adding “space cadet” and “gag me with a spoon” permanently to the lexicon—explored Valley kids’ longing to be part of the supposedly cooler, star-studded world of Hollywood, so close but so far away.

Calabasas (population 23,058) was said to be a typical Valley hamlet, but with more celebrity residents, including (then) Britney Spears, Will Smith and Jada Pinkett and their already famous kids, country singer LeAnn Rimes, Nikki Sixx of Mötley Crüe and Richie Sambora of Bon Jovi, former Nickleodeon star Amanda Bynes. . . . Weirdly, Calabasas was also a Fertile Crescent for reality television. One of the first big reality shows featuring a (sort of) famous person, Jessica Simpson, and her then husband Nick Lachey, was shot there: Newlyweds: Nick and Jessica (2003–2005). So was Spears’ burps-and-all look at life with her then husband Kevin “K-Fed” Federline: Britney and Kevin: Chaotic (2005). And so is the Queen Mary of all reality television: Keeping Up with the Kardashians (2007–). In each of these shows, Calabasas looks like Xanadu with SUVs, a place of SoCal-style easy living, where everybody’s wealthy.

And Calabasas is rich, relatively speaking; the median income is about $116,000, more than twice the national average. According to the online Urban Dictionary (albeit an opinionated source), “The typical Calabasas resident is young, rude, rich. . . . You’ll see. . . 10-year-old girls with their Louis Vuitton purses and Seven jeans giggling to their friends on their iPhones.”

It was interesting to see how media coverage of the Bling Ring was playing up the burglars as “rich.” Said the New York Post: “A celebrity-obsessed group of rich reform-school girls allegedly waged a year-long, A-list crime spree through the Hollywood Hills, ripping off millions in cash and jewels from the mansions of such stars as Paris Hilton and Lindsay Lohan. . . .” People always seemed fascinated by stories about rich kids. I should know, I’d done a few myself. Editors seemed to like such stories, especially if the kids were behaving badly. Readers seemed to love to hate these kids. I once received a letter, in response to one of my stories about bad rich kids in Manhattan, from a World War II veteran demanding, “Can the prep school gangsters fly a B-29?” That was a very good question.

But it was clear the appeal of the Bling Ring story wasn’t just the wealthy kids; it was one of those stranger-than-fiction tales that hits the Zeitgeist at its sweet spot, with its themes of crime, youth, celebrity, the Internet, social networking (the kids had been advertising their criminal doings on Facebook), reality television, and the media itself, all wrapped up in one made-for-TV movie (which didn’t exist yet, but would). The wall between “celebrity” and “reality” was blurring faster than you could say “Kim Kardashian.” Celebrities were now acting like real people—making themselves accessible nearly all

the time; even Elizabeth Taylor tweeted (“Life without earrings is empty!”)—and real people were acting like celebrities, with multiple Facebook and Twitter accounts and sometimes even television shows documenting their—real and scripted—lives. It was all happening at warp speed, affecting American culture on a cellular level and, if you wanted to get fancy about it, begging the age-old question of “What is a self?” (And, “If I post something on Facebook and no one ‘likes’ it, do I exist?”) The Bling Ring had crossed a final Rubicon, entering famous people’s homes, and their boldness felt both disturbing and somehow inevitable.

News of the kids, so far, didn’t offer many details, and no interviews with the suspects themselves. The six who had been arrested in connection with the burglaries were Rachel Lee, 19—“the gang’s alleged mastermind,” according to the Post; Diana Tamayo, 19; Courtney Ames, 18; Alexis Neiers, 18; Nicholas Prugo, 18; and Roy Lopez, 27, who had been identified as a bouncer. Lee, Prugo, and Tamayo all reportedly knew each other from Indian Hills, an alternative high school in Agoura Hills (it was “a couple of exits away” from Calabasas, a Southern Californian had told me). The only one who had been formally charged was Prugo, with two counts of residential burglary of Lohan and reality star Audrina Patridge (she was one of the girls on The Hills, a sort of real-life Melrose Place about vacuous twentysomethings in L.A.). Prugo was facing up to twelve years in prison. Another suspect in the case, Jonathan Ajar—a.k.a. “Johnny Dangerous,” 27—who had been identified as a nightclub promoter, was wanted for questioning. TMZ was saying he was “on the run.”

The kids’ mug shots didn’t tell much, either, except that they all looked very young and bedraggled in the way people do when they get hauled into jail. Prugo looked rather cunning (later, he would admit that the black-and-white striped T-shirt he was wearing in his mug shot belonged to Orlando Bloom). Lee and Ames—a brown-haired, light-eyed girl, neither pretty nor plain—looked scared. Tamayo wore a defiant expression. Lopez looked thuggish and resigned.

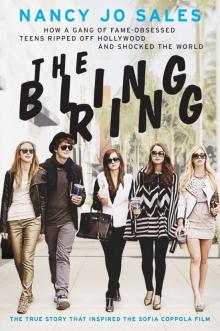

The Bling Ring

The Bling Ring